Sewing is becoming a popular activity in our Montessori studio. Knowing how to sew is a useful skill with lifelong practical applications and benefits. It requires concentration, focus, and problem solving, and helps develop hand-eye-coordination and fine motor skills. For these reasons, sewing falls under Practical Life activities in the Montessori curriculum. More specifically, sewing encourages children to care for themselves, meet their own needs, and foster functional independence. The goal is that one day a child notices there is a hole in his favorite socks, and follows up this observation with action—fixing it himself!

At the beginning of the year, we start with a variety of lacing tools, from simple beading to continuous lacing frames. When the child is ready, we introduce a blunt needle and thread and begin sewing on sturdy material, such as cardboard or cardstock, with premade holes. The trick is to follow the pattern and build muscle memory for basic stitching. From there, we introduce soft fabrics such as burlap and felt for a child to begin strengthening her hand by puncturing the holes independently and applying the movements she has been practicing.

This week, there are a variety of sewn mittens hanging on our display board outside the Montessori studio. Sewing also allows for children’s creativity to shine! The learners have fun picking fabric and deciding which color thread to use or which beads or buttons to add.

On cold, wintry days, this is a wonderful activity to replicate at home. Start sewing in your home with this great beginners board or these lacing frames. And check out Sewing in the Montessori Classroom for more information about the science behind sewing and projects for all ages.

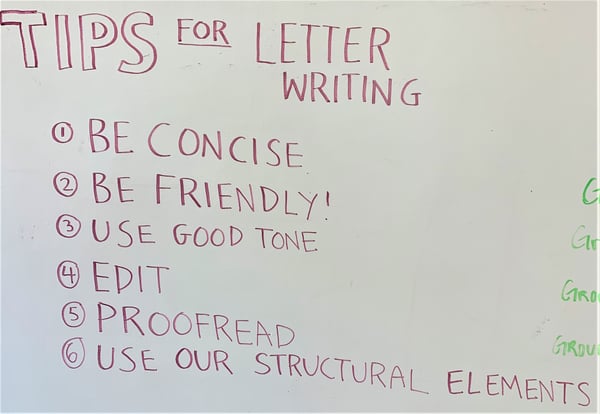

As part of our writer’s workshop, “Letter to a Hero,” the learners dove a little bit deeper into the elements of a letter and the best practices that will help them write polished letters to their heroes. We began with a broad question: what are the most important parts of a letter? The learners were put into two groups and had 20 minutes to research, explore, and create a list of the important parts of a letter for discussion. As a group, they came up with the following:

Young children are learning how to hear and reproduce the sounds of spoken language. In order to write, they need to know how to break down words into phonemes, the small units of sound we associate with letters and combinations of letters.

Opportunities for rhyming help learners isolate different chunks of sounds. In the studio, we sing songs like “Down by the Bay” or “Willoughby Wallaby Woo,” which are fun for learners and help them hear the component parts of words. If you’d like to sing at home, it goes like this:

Willoughby wallaby wusan,

An elephant sat on Susan!

Willoughby wallaby wack,

An elephant sat on Jack!

This week learners also enjoyed singing Apples and Bananas, which helps children hear long and short vowel sounds.

I like to eat, eat, eat apples and bananas

I like to eat, eat, eat apples and bananas

I like to ate, ate, ate ay-ples and ba-nay-nays

I like to ate, ate, ate ay-ples and ba-nay-nays

I like to eat, eat, eat ee-ples and bee-nee-nees

I like to eat, eat, eat ee-ples and bee-nee-nees

Etc.

Enjoy these silly songs with your learner!

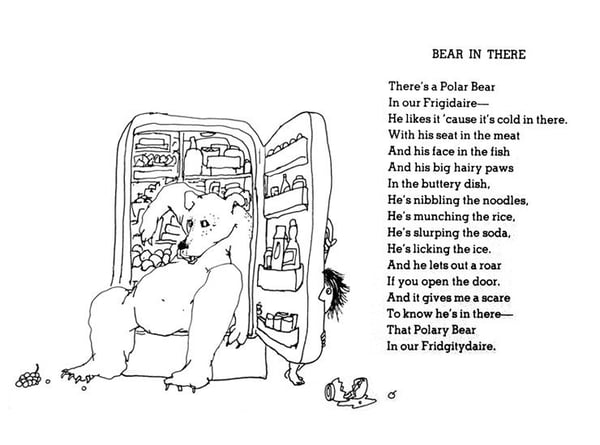

Poetry is powerful, and in the Montessori studio, that power is recognized. Poems are easy to memorize, and when children are able to recite a poem, it gives them a sense of pride and accomplishment. So far, our Montessori learners know three poems: “Bear in There” by Shel Silverstein, “Winter Animals” (see images above), and our “Thank You Poem,” which we recite aloud before we eat a meal together (see Thanksgiving blog post for poem).

“You get out what you put in.”

It’s a straightforward sentiment, and one that is applicable to nearly any endeavor. This concept was brought up during CrossFit as a way to explain the benefits of pushing yourself. Coach Andrew said:

This is going to be a tough workout today, and you have options. You can give it your all and use proper form on every jumping jack and and sit up, or you can go on autopilot. It’s your choice, but, at the end of the day, will you want to look back and feel like there was something you could’ve worked harder at? Will you want to feel like you’re not allowing yourself to get as good as you can possibly be?

At close that day, the idea of getting out what you put into something was raised again. The guides asked the learners what that meant to them. One learner responded, “It means the benefits at the end are equal to how much effort you put in.” A lot of heads nodded in agreement.

The discussion then shifted to talking about times at Acton that the learners have seen this principle at work. One learner responded that Khan math requires a lot of time to understand the concepts, but that the more time put in, the easier it is to build on the material and make progress faster. Another said that writer’s workshop and the writing process is an example of getting out what you put in: “If you don’t follow all of the steps properly in brainstorming, drafting and editing, your work won’t be as good as it could be.”

At Acton, learners regularly face challenges that require time, effort, and focus. There might be areas of core skills they prefer over others, and there might be particular writing genres they find easier to devote energy to. They might dislike certain games and be excited to play others for hours on end. The key is understanding that they have the capacity to put their full effort into anything they choose.

Going to school in the nation’s capital can be exciting! Learners are naturally curious about what they observe on their way to school, in our outdoor space, and on our excursions. They are particularly inquisitive when it comes to low-flying helicopters. Is that the President? Where is it going and where is it coming from? Guides, do you have the answers?

Guides try not to answer questions as part of our role in the studio. Questions like these, though, we are often unable to answer!

The beginning of a new semester encourages learners to cultivate this curious mindset and apply it to their learning. What are we learning in quest and writer’s workshop? What will our studio look like in six weeks at our next exhibition? What’s next for me in core skills?

Not only does this mindset help with goal setting and maintaining excellence in our studio, but it pushes learners to seek answers to their questions. In the architecture quest this session, learners will investigate the structure of our school building and then design their own dream studio. If they choose, learners can also submit a design to be considered for the new Acton middle school studio.

Learners will also apply their curiosity to this session’s writer’s workshop, podcasts. In their podcasts, learners can tell a fictional story, host an imaginary interview with an expert, or present research on a topic of interest to them. Many learners are already using this writer’s workshop as an opportunity to seek answers to their many questions.

What’s the history of the alphabet? How can you sneak candy into the movies? What is the meaning behind this song? All these are questions that learners will seek to answer in a podcast format this session!

"The hands," wrote Dr. Maria Montessori, "are the instrument of man's intelligence." Squishing, rolling, sculpting, molding . . . young children love to play with playdough. Add some props from around the home and playdough play becomes a powerful way to support your child’s learning. This simple preschool staple lets children use their imaginations and strengthen the small muscles in their fingers—the same muscles they will one day use to hold a pencil and write.

Through manipulations, children develop eye-hand coordination, the ability to match hand movement with eye movement. They also gain strength and improve dexterity in their hands and fingers, critical areas of physical development for writing, drawing, using scissors, zipping zippers and buttoning buttons.

When children use this malleable material, they explore ideas and try different approaches until they find one that works. They compare and contrast objects ("Mine is a fat pancake and yours is skinny”), actions ("Let’s scrape it, like this”), and build connections with patterns, lines, and shapes ("We were making a snake, but now it looks like a really long road”). In their experimenting, children come up with their own ideas, satisfy their curiosity, and analyze problems.

Add sand or water to the playdough and then talk about how this new kind of dough looks and feels. Introduce words like texture, grainy, smooth, and lumpy. Your child might declare, "I’m making this flat!” as she pushes down on playdough with the palm of her hand. Or she may say, "I’m making it soft,” as she adds water to dry playdough to make it more pliable.

Make your own batch of playdough at home and see for yourself!

INGREDIENTS:

Montessori learners are beginning to understand the grace and courtesy associated with a handshake. At our morning group gathering, we go around the circle turning to our neighbor to offer our right hand (mostly) as a way to acknowledge each person’s presence with consciousness and compassion. They achieve a grip, make eye contact, and often smile before saying “good morning."

Are you a giver or a taker? Are you an explorer, a puzzler, or a data collector? How did people who lived in ancient civilizations, like Sparta and Athens, build their identities? These are all questions learners addressed this week during launch, quest, and civilizations respectively.

Our conversations challenged learners to consider whether they construct their identity based on their values, their actions, or their thoughts and feelings. Learners said they identify themselves and others based on actions. If you want to be considered kind, treat people with kindness; if you want to be a mathematician, master your math skills; if you want to be an athlete, play sports.

The Montessori learners are excited to explore different artists as well as different types of art. The learners focused on the French artist Henri Matisse, who was best known for his paintings and a new form of art he developed using paper and scissors when he was too ill to paint.